A 10-year retrospective on the multimillion-dollar scheme that rocked the Monadnock Region

| Published: 03-30-2022 11:41 AM |

In March of 2012, after being confronted by his clients, investment broker Aaron Olson of Rindge turned himself in to the government and made a shocking confession – he had been running one of the most-significant Ponzi schemes in New Hampshire history, and had lost $22.8 million in invested funds.

Mark Zuckerman, assistant U.S. attorney and chief of the criminal division for the U.S. Attorney’s Office, was the prosecutor on the case that eventually came against Olson and said he remembers it well.

“It's been certainly ranked as one of the more-significant fraud cases that's been prosecuted in recent memory,” Zuckerman said in an interview with the Ledger-Transcript. “$22 million is obviously a significant sum, and the impact on the victims was pronounced and severe.”

In comparison, the largest investment Ponzi scheme in New Hampshire’s history was the Financial Resources Mortgage fraud, in which a group of 150 investors lost around $30 million in 2009. One of the reasons the revelation of the losses was so shocking was because most, if not all, of the victims were close to Olson, including family members and members of his church.

It’s what’s known as an affinity scheme, Zuckerman said.

“The victims have an association or affinity with the schemer. You need to know someone to get the opportunity to invest in the scheme, and it makes it seem more exclusive,” Zuckerman said.

One of the most famous Ponzi schemes of all time, executed by Bernie Madoff, who defrauded thousands of investors of billions of dollars over 17 years in the 1990s and 2000s, followed a similar model, Zuckerman said.

“You had to be exclusive, ‘in the club,’ to get an introduction,” Zuckerman said. “That case stands as an outlier as the largest scheme in U.S. history, but it shared attributes with what was going on here. You had to know me or someone who knows me to get in on the scheme.”

Article continues after...

Yesterday's Most Read Articles

Zuckerman said other schemes cast a wider net, and rely on a greater volume of smaller investments. Olson, Zuckerman said, appeared to focus on individuals that had larger amounts of capital to invest.

“Every scheme is different. Here, the focus was obviously on people that had resources to invest, and were targeted in that way, and that’s part of how this scheme was focused,” Zuckerman said.

According to court documents, from 2007 to 2010, Olson owned two unlicensed businesses that invested in commodity, stock and bond markets. By 2010, Olson had amassed a large amount of funds from investors – $27.8 million.

But those who were entrusting their funds with Olson didn’t know everything. Olson was not a licensed broker, and his businesses were not registered to trade in New Hampshire.

Following an investigation by the New Hampshire Bureau of Securities into his business, KMO, Olson shut them down, renamed it to AEO and reopened it in Massachusetts, but continued to run the business out of his Rindge home.

While investors were getting reports of significant returns on their investments, the truth was very different. In 2011, Olson’s investments began to fail. Rather than tell his clients about the losses, Olson began to mislead them about how well the investments were doing.

Olson converted about $2.6 million of the funds for his own use. For those invested with him, he would disguise gains made by one investor as “earnings” to other investors, and provided them with false reports.

By 2012, Olson could no longer keep up with the scheme, and some investors became suspicious and confronted him, at which point Olson turned himself in and made a full confession.

But by that time, he had lost millions in his clients’ funds.

Olson was eventually charged in relation to the scheme, though not directly. He was charged with tax evasion from 2007 through 2010, for failing to report the illicit income he was gaining from the scheme.

On March 9, 2015, Olson pled guilty to all four counts of attempted tax evasion. In a plea agreement, Olson agreed to pay restitution to his victims and serve a range of 42 to 60 months in prison. While his counsel at the time argued for the lighter end of the sentence, citing Olson’s cooperation with the investigation, and that he had shown remorse since his confession, the court sentenced him to the longest sentence stipulated in the agreement – 60 months.

Olson’s original plea agreement allowed up to five years in prison for each charge – 20 years total for all four charges of tax evasion – but Olson believed it to be five years total. Olson withdrew his plea, and a renegotiated agreement capping the prison time at five years total, followed by up to three years of supervised release, was accepted by the court.

He was also fined $250,000 in unpaid taxes, plus the cost of prosecution, and U.S. District Court has ordered restitution be made to Olson’s investors – a total of $22.8 million.

Olson did not immediately start his sentence, and despite pleading guilty in exchange for a plea agreement on his sentencing, appealed the case and went through several lawyers, citing inadequate counsel. Olson unsuccessfully attempted to sue one of his lawyers, Robert S. Carey, for malpractice, for inaccurately representing the potential sentence of the proposed plea agreement, but the suit was dismissed by the court.

He began serving his sentence in 2016.

Olson had 81 recorded victims. At least four investors lost more than $1 million, with a large amount of investors losing several hundred thousand dollars.

“For some individuals, it was very significant,” Zuckerman said. “I didn’t personally speak with all 81 victims, but I did speak with a number of them. For some, in particular, it was their life savings. It was traumatic and tremendously significant for them.”

According to Olson’s restitution schedule, he is required to pay $500 per month, which started immediately following his release from prison. That payment would address the principal restitution payment after 3,801 years.

“It’s often very difficult,” Zuckerman said of victims being made whole after a Ponzi scheme like the one run by Olson. “If the assets have been dissipated, as they were in this case, it’s very difficult. The money is just gone.”

But the restitution order is still important, Zuckerman said, because if Olson’s financial circumstances change, it allows for any “windfalls” to be given to his victims.

“Should he come into money, whether it be through winning the lottery, as unlikely as that is, or receiving an inheritance, it would have to be reported, and that money would be allocated to the restitution. This is one we are paying close attention to,” Zuckerman said.

Ashley Saari can be reached at 603-924-7172 ext. 244 or asaari@ledgertranscript.com. She’s on Twitter @AshleySaariMLT.

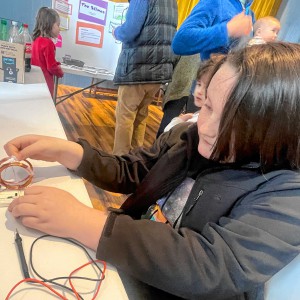

Young scientists show off their stuff at science fair in Francestown

Young scientists show off their stuff at science fair in Francestown Peterborough Farmers’ Market opens for the season

Peterborough Farmers’ Market opens for the season New Ipswich Congregational Church celebrates paying off mortgage

New Ipswich Congregational Church celebrates paying off mortgage Deb Caplan builds a business out of her creative passion

Deb Caplan builds a business out of her creative passion