Harris Center program outlines steps to help kestrels

| Published: 08-30-2023 12:55 PM |

The Harris Center for Conservation and Education unveiled a new modeling software being used to combat falling kestrel populations nationally and regionally during an update on the American Kestrel Partnership Tuesday night.

Presented on Zoom to 20 participants, the update sought to educate attendees on the status of the threatened species of falcon, as well as what the community can do to help preserve their habitats. Harris Center bird conservation intern Will Stollsteimer, who has spent the last year with the center and has now returned to his native Pennsylvania to continue his work, gave the presentation.

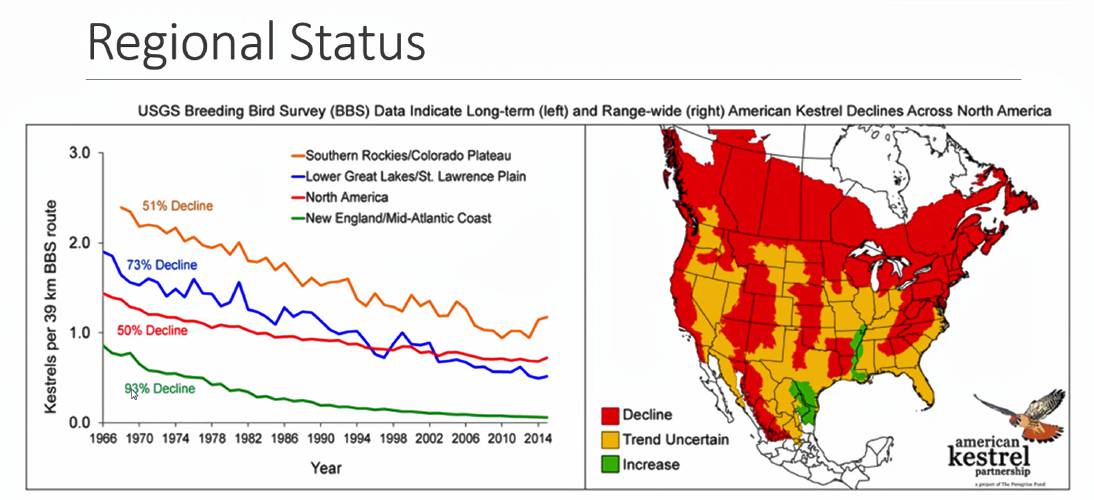

The main points of the presentation, as laid out by Stollsteimer, pertained to the ecology of the American kestrel as well as its conservation status, the initiative of the Harris Center’s kestrel project and what the participants can do to help. He began the update with background on the species, sharing figures about the decline of population observed in recent decades.

“Data from Cape May back in the 1970s have had single-day counts of up to 25,000 kestrels, which is ridiculous by today's standards,” said Stollsteimer. “It's not something we would ever expect over at Pack Monadnock. If we have a day with double digits of kestrels, that was always really exciting for me, and I don't know that I ever witnessed the day with triple digits of kestrels. That may not be something we see all that often nowadays.”

Stollsteimer went on to share figures relating to the decline of the species and the connection to high juvenile mortality rates. He explained that despite the seemingly positive 45% mortality for juveniles, is not truly representative of reality. The figure does not reflect discrepancies in hatching time within a clutch of several eggs, and that earlier-hatched eggs “may have a significantly higher success rate than the last bird of a clutch to hatch.” Stollsteimer then focused on the unique habitat of the bird, and emphasized that the preferred nesting practices of the kestrel makesthem an early and easy victim of development.

Kestrels nest in existing cavities, such as snarled limbs of trees. These habitats have been largely eliminated due to being a danger to the public, and are disappearing rapidly. The kestrel also forages in open planes and fields, which is a rapidly disappearing habitat due to development.

“We can see that grassland habitats, especially in the Northeast, where development is starting to take over, we're seeing lots of examples of urban sprawl. You're getting habitats that are very easy to develop over because they're large, open pastures, rather than trying to cut down entire forests to build a mini-mall,” said Stollsteimer. “It's much easier to build over lots that already have open space, so it's one of our quickest-disappearing habitats and this bird is suffering from that.”

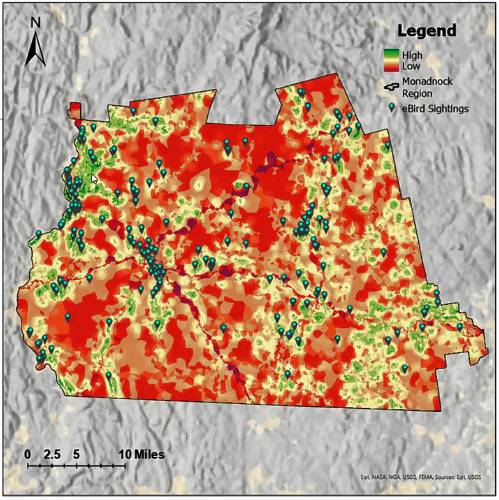

Stollsteimer concluded the presentation with promising examples of the center’s new Global Information System (GIS) modeling. The system allows for Stollsteimer and other scientists to pick out kestrel habitats and overlay areas of danger for the species, such as large interstates. The model is then used to pick sites that nest boxes would be safe to build, and volunteers then help construct and place these boxes. Early signs indicate that these placements have been promising, according to Stollsteimer, yielding eggs and chicks at later checks of the sites.

Article continues after...

Yesterday's Most Read Articles

These nest boxes are constructed via fundraising and volunteers, and the GIS tracking can also be aided by the community. The eBird program has allowed recreational birders to provide their kestrel sightings to the center and aid in understanding the current state of their habitats and migratory patterns.

Before fielding questions and comments from the audience, including enthusiasts volunteering their properties and municipalities to build nest boxes, Stollsteimer shared his enthusiasm and hope he took away from the project.

“The biggest thing I can take away from this entire project and all of my extensive research is that there's so much left to learn about the species,” said Stollsteimer. “There's endless projects that we can tackle. And all of this is made possible by everyone here at the Harris Center, and everyone who supports the project… and obviously everyone who supported these projects such as landowners who offered up their properties.”

ConVal committee begins to study withdrawal process

ConVal committee begins to study withdrawal process Education committees gather in Dublin

Education committees gather in Dublin Francestown welcomes new Library Director Beth Crooker

Francestown welcomes new Library Director Beth Crooker Temple unlikely to hold special Town Meeting on ConVal withdrawal

Temple unlikely to hold special Town Meeting on ConVal withdrawal