Latest News

PHOTOS: Cleaning up Memorial Park

PHOTOS: Cleaning up Memorial Park

Martin discusses experience in China

Martin discusses experience in China

Harris Center conducts veterans hike at Jack’s Pond in Hancock

A group of veterans from around the Monadnock region, led by Susie Spikol of the Harris Center for Environmental Education, learned the little-known history of Hancock’s Jack’s Pond Sunday as part of the Harris Center’s veterans hiking program.The...

Mark Fernald’s maple syrup named best for third time in Ledger-Transcript contest

Mark Fernald of Sharon took home his second consecutive win and third overall among the judges at the Monadnock Ledger-Transcript’s 42nd annual maple syrup contest Saturday.The event was held at the Bantam Grill in Peterborough, where attendees had...

Sports

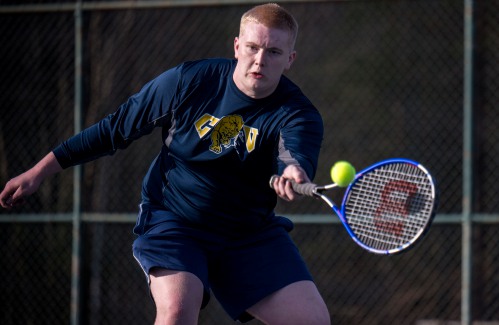

ConVal boys’ tennis looks to build experience

The ConVal boys’ tennis team comes into the season with almost no experience and a lot of work to do, but coach Mike Young relishes the challenge of building a full roster of players from the ground up. “You’ve got to start from the basics, which...

Opinion

Letter: Ban is not a political issue

Jeremy Margolis' article (“Senate OKs trans women sports ban,” April 9) struck me and, as a woman, I bristled.The article begins, "In the latest victory for Republicans… ." Why must this be presented politically? What has happened to humanity? This is...

Margaret Nelson: View From the River – The gift of volunteers

Margaret Nelson: View From the River – The gift of volunteers

Business

Deb Caplan builds a business out of her creative passion

When she moved from Florida to New Hampshire in 2011, Deb Caplan, a lifelong creative, was thrilled to find that her new hometown of Peterborough was a major hub for for creativity and the arts in the Monadnock region.“I love living around here. There...

Parker and Sons Coffee Roasting in Peterborough strives to create the perfect coffee

Parker and Sons Coffee Roasting in Peterborough strives to create the perfect coffee

Happy Hardware looks to put the fun in hardware shopping

Happy Hardware looks to put the fun in hardware shopping

Old Homestead Farm proposes short-stay cabins to supplement event business

Old Homestead Farm proposes short-stay cabins to supplement event business

Arts & Life

DubHub April art show features Loy and Andrews

dublinDubHub hosting April art showIn April, the Dublin Community Center, 1123 Main St. will feature the works of artists Eva-Lynn (“Evie”) Loy and Daniel Andrews, both of whom reside in Keene.A public reception is scheduled for Friday, April 12, from...

Optimist Café to display Barbara Danser paintings

Optimist Café to display Barbara Danser paintings

‘Puppet’ tells Antrim native Dan Hurlin’s story

‘Puppet’ tells Antrim native Dan Hurlin’s story

Exhibition on Screen features Sargent

Exhibition on Screen features Sargent

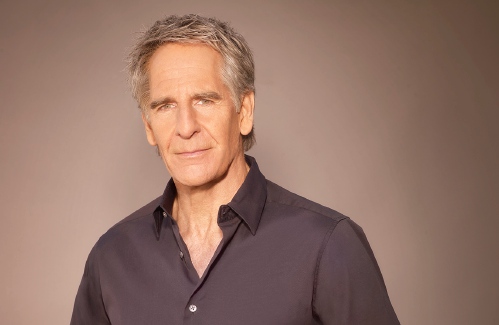

Scott Bakula starring in Peterborough Players’ ‘Man of La Mancha’

Scott Bakula starring in Peterborough Players’ ‘Man of La Mancha’

Obituaries

Katherine W. Allen

Katherine W. Allen

Francestown NH - Katherine W. Allen of Francestown, NH and most recently of Hailey, Idaho died peacefully on February 16, 2024 at the age of 94. Born April 26, 1929 she was the daughter of ... remainder of obit for Katherine W. Allen

Kenneth Noyd

Kenneth Noyd

Bath, ME - Kenneth Herbert Noyd was born November 27, 1930 in Norwood, Massachusetts. Ken passed away on April 7, 2024 at the age of 93 near Bath, Maine, after enjoying heartfelt conversati... remainder of obit for Kenneth Noyd

Karen B. Ayers

Karen B. Ayers

, 80 Jaffrey, NH - Karen Backstrom Ayers of Jaffrey, NH, passed away in Keene, NH, on April 12, 2024. Karen was born on September 9, 1943, in Pittsburgh, PA, a daughter to Melvin Leslie and ... remainder of obit for Karen B. Ayers

Donald Engelbert

Donald Engelbert

Sandown NH - Donald Craig Engelbert, 74, of Sandown, NH died on December 11, 2023, at his home surrounded by his family, accepting that cancer treatments were no longer beneficial and there... remainder of obit for Donald Engelbert

Jack Kidd and Kidd Gloves make donation to Mt. Monadnock Little League

Jack Kidd and Kidd Gloves make donation to Mt. Monadnock Little League

Old Homestead Farm in New Ipswich requests variance for short-term rental cabins

Old Homestead Farm in New Ipswich requests variance for short-term rental cabins

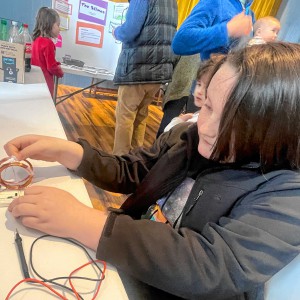

Young scientists show off their stuff at science fair in Francestown

Young scientists show off their stuff at science fair in Francestown

Peterborough Farmers’ Market opens for the season

Peterborough Farmers’ Market opens for the season

New Ipswich Congregational Church celebrates paying off mortgage

New Ipswich Congregational Church celebrates paying off mortgage

HIGH SCHOOL SPORTS ROUNDUP: Tasha MacNeil leads the way for ConVal at Pelham Invita

HIGH SCHOOL SPORTS ROUNDUP: Tasha MacNeil leads the way for ConVal at Pelham Invita

Grey Horse Candle Company opens Peterborough storefront

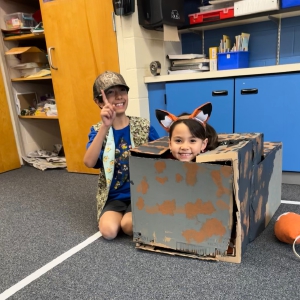

Grey Horse Candle Company opens Peterborough storefront JGS Destination Imagination teams participate in regionals

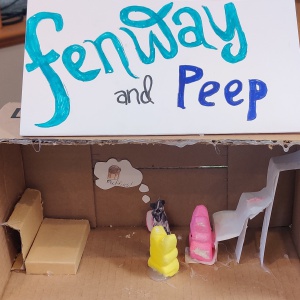

JGS Destination Imagination teams participate in regionals Hancock Town Library’s Literary Peep Diorama contest draws most-ever entrants

Hancock Town Library’s Literary Peep Diorama contest draws most-ever entrants Construction of joint Peterborough/Jaffrey water facility over 50% complete

Construction of joint Peterborough/Jaffrey water facility over 50% complete

Monadnock Valley Patriots compete in state Special Olympics basketball tournament

Monadnock Valley Patriots compete in state Special Olympics basketball tournament Jed and Summer Bentley excel at Nordic skiing championships

Jed and Summer Bentley excel at Nordic skiing championships Marty Gitlin to present “The Ultimate Red Sox Nation” April 15 at Chamberlin Free Public Library in Greenville

Marty Gitlin to present “The Ultimate Red Sox Nation” April 15 at Chamberlin Free Public Library in Greenville