Latest News

Franklin Pierce University names valedictorian and salutatorian

Franklin Pierce University announced that Madeline Ward has been named valedictorian for the Class of 2024, and Ryan Walker has been named the class's salutatorian.Ward, from Wolfeboro, majored in biology while also earning minors in spanish and...

Harris Center conducts veterans hike at Jack’s Pond in Hancock

A group of veterans from around the Monadnock region, led by Susie Spikol of the Harris Center for Environmental Education, learned the little-known history of Hancock’s Jack’s Pond Sunday as part of the Harris Center’s veterans hiking program.The...

Most Read

Peterborough Planning Board approves 14-unit development near High Street

Peterborough Planning Board approves 14-unit development near High Street

Peterborough firefighters continue fishing derby tradition

Peterborough firefighters continue fishing derby tradition

Franklin Pierce students help foster literacy at Rindge Memorial School

Franklin Pierce students help foster literacy at Rindge Memorial School

ConVal attorney answers withdrawal questions

ConVal attorney answers withdrawal questions

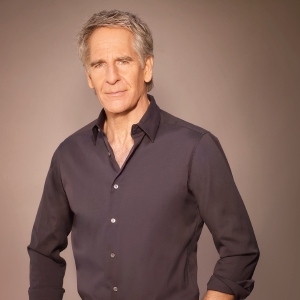

Scott Bakula starring in Peterborough Players’ ‘Man of La Mancha’

Scott Bakula starring in Peterborough Players’ ‘Man of La Mancha’

HOUSE AND HOME: The Old Parsonage in Antrim is a ‘happy house’

HOUSE AND HOME: The Old Parsonage in Antrim is a ‘happy house’

Editors Picks

HOUSE AND HOME: The Old Parsonage in Antrim is a ‘happy house’

HOUSE AND HOME: The Old Parsonage in Antrim is a ‘happy house’

Former home of The Folkway in Peterborough is on the market

Former home of The Folkway in Peterborough is on the market

Two Jaffrey-Rindge Destination Imagination teams move on to Globals

Two Jaffrey-Rindge Destination Imagination teams move on to Globals

Parker and Sons Coffee Roasting in Peterborough strives to create the perfect coffee

Parker and Sons Coffee Roasting in Peterborough strives to create the perfect coffee

Sports

Conant girls’ tennis continues to seek improvement

When Gloria Morison wakes up in the middle of the night, her mind turns to tennis.That's a good thing for her Conant girls' tennis team, as they can benefit from her late-night musings. Before Tuesday's home showdown with visiting Kearsarge, it was...

Jack Kidd and Kidd Gloves make donation to Mt. Monadnock Little League

Jack Kidd and Kidd Gloves make donation to Mt. Monadnock Little League

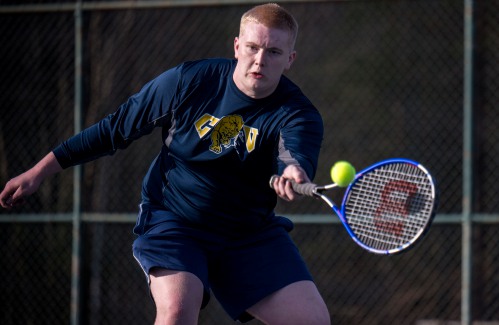

ConVal boys’ tennis looks to build experience

ConVal boys’ tennis looks to build experience

Opinion

Viewpoint: Jay Schechter – ConVal agreement no longer works

On Wednesday, April 10, the Monadnock Center For History and Culture and Monadnock Ledger-Transcript sponsored a Community Conversation. Several members of the Dublin Education Advisory Committee attended.The presentation was billed as an event to ask...

Business

Deb Caplan builds a business out of her creative passion

When she moved from Florida to New Hampshire in 2011, Deb Caplan, a lifelong creative, was thrilled to find that her new hometown of Peterborough was a major hub for for creativity and the arts in the Monadnock region.“I love living around here. There...

Parker and Sons Coffee Roasting in Peterborough strives to create the perfect coffee

Parker and Sons Coffee Roasting in Peterborough strives to create the perfect coffee

Happy Hardware looks to put the fun in hardware shopping

Happy Hardware looks to put the fun in hardware shopping

Grey Horse Candle Company opens Peterborough storefront

Grey Horse Candle Company opens Peterborough storefront

Arts & Life

Jaffrey kicks off Earth Week with no-waste potluck and environmental speakers

There were no paper plates or plastic utensils to be seen during the Jaffrey Climate Initiative and Jaffrey Conservation Commission Earth Day kickoff potluck on Tuesday, where participants were asked to bring their own plates and utensils for a...

Gnome Notes: Emerson Sistare – Amor Towles weaves tapestry in ‘Table for Two: Fictions’

Gnome Notes: Emerson Sistare – Amor Towles weaves tapestry in ‘Table for Two: Fictions’

Jaffrey Civic Center hosting Heart of the Arts

Jaffrey Civic Center hosting Heart of the Arts

Project Shakespeare to present ‘The Miraculous Journey of Edward Tulane’

Project Shakespeare to present ‘The Miraculous Journey of Edward Tulane’

The Thing in the Spring returns May 16

The Thing in the Spring returns May 16

Obituaries

Bonnie Paquette

Bonnie Paquette

Bennington, NH - Bonnie (Adams) Paquette, 65, of Bennington NH, passed away on April 13th, 2024, at Concord Hospital, surrounded by her family. The daughter of Ruth Greeley and Robert Adams... remainder of obit for Bonnie Paquette

Katherine W. Allen

Katherine W. Allen

Francestown NH - Katherine W. Allen of Francestown, NH and most recently of Hailey, Idaho died peacefully on February 16, 2024 at the age of 94. Born April 26, 1929 she was the daughter of ... remainder of obit for Katherine W. Allen

Kenneth Noyd

Kenneth Noyd

Bath, ME - Kenneth Herbert Noyd was born November 27, 1930 in Norwood, Massachusetts. Ken passed away on April 7, 2024 at the age of 93 near Bath, Maine, after enjoying heartfelt conversati... remainder of obit for Kenneth Noyd

Karen B. Ayers

Karen B. Ayers

, 80 Jaffrey, NH - Karen Backstrom Ayers of Jaffrey, NH, passed away in Keene, NH, on April 12, 2024. Karen was born on September 9, 1943, in Pittsburgh, PA, a daughter to Melvin Leslie and ... remainder of obit for Karen B. Ayers

Antrim Fire Department selling used truck

Antrim Fire Department selling used truck

Jarvis Coffin: Off the Highway – Calmly on the waters

Jarvis Coffin: Off the Highway – Calmly on the waters

Words About Wilton: Gail Hoar – Protecting and serving

Words About Wilton: Gail Hoar – Protecting and serving

HIGH SCHOOL SPORTS ROUNDUP: Tasha MacNeil leads the way for ConVal at Pelham Invita

HIGH SCHOOL SPORTS ROUNDUP: Tasha MacNeil leads the way for ConVal at Pelham Invita