Fassett Farm Nursery in Jaffrey focuses on native plants

Fassett Farm Nursery in Jaffrey, which has a focus on growing and selling native plants, is back for its second season starting May 4 with a new storefront, expanded hours and new consultation offerings.The nursery is owned by Aaron Abitz, and run on...

UPDATE: Drivers identified in Jaffrey dump truck crash

A collision between a sedan and a dump truck on Route 202 in Jaffrey Wednesday afternoon caused a significant fuel spill across the highway and led to one driver being taken to the hospital.According to police reports, a 2023 Nissan Rogue, driven by...

Most Read

UPDATE: Drivers identified in Jaffrey dump truck crash

UPDATE: Drivers identified in Jaffrey dump truck crash

Conant baseball shows its strength in win over Mascenic

Conant baseball shows its strength in win over Mascenic

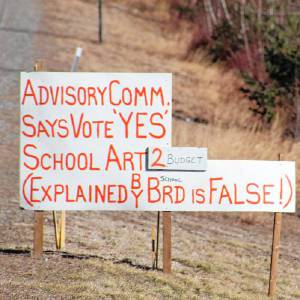

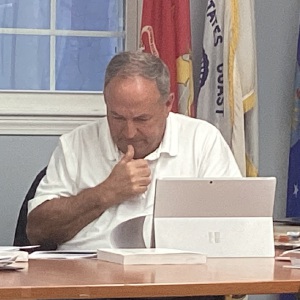

Group looks to close divide in Mascenic district

Group looks to close divide in Mascenic district

Bernie Watson of Bernie & Louise dies at 80

Bernie Watson of Bernie & Louise dies at 80

Rindge Recreation Department organizes a trip to Converse Meadow

Rindge Recreation Department organizes a trip to Converse Meadow

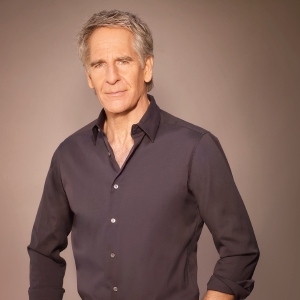

Scott Bakula starring in Peterborough Players’ ‘Man of La Mancha’

Scott Bakula starring in Peterborough Players’ ‘Man of La Mancha’

Editors Picks

HOUSE AND HOME: The Old Parsonage in Antrim is a ‘happy house’

HOUSE AND HOME: The Old Parsonage in Antrim is a ‘happy house’

Former home of The Folkway in Peterborough is on the market

Former home of The Folkway in Peterborough is on the market

Two Jaffrey-Rindge Destination Imagination teams move on to Globals

Two Jaffrey-Rindge Destination Imagination teams move on to Globals

Old Homestead Farm in New Ipswich requests variance for short-term rental cabins

Old Homestead Farm in New Ipswich requests variance for short-term rental cabins

Sports

Katalina Davis dazzles in Mascenic shutout win

The Mascenic softball team soared to a 7-0 shutout win over regional and interdivisional rival Conant thanks to a dazzling performance on both sides of the ball from senior pitcher Katalina Davis. “When Kat’s on, they’re not hitting, so she was...

LOCAL SPORTS ROUNDUP: Conant girls’ tennis gets first win

LOCAL SPORTS ROUNDUP: Conant girls’ tennis gets first win

Conant girls’ tennis continues to seek improvement

Conant girls’ tennis continues to seek improvement

Jack Kidd and Kidd Gloves make donation to Mt. Monadnock Little League

Jack Kidd and Kidd Gloves make donation to Mt. Monadnock Little League

Opinion

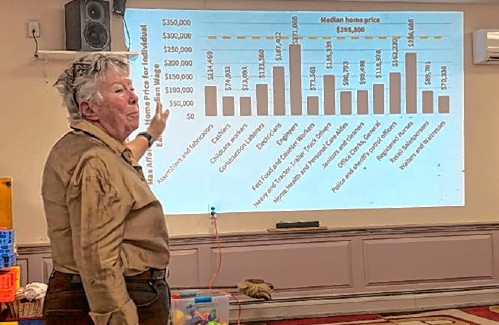

Opinion: It’s time to properly fund education

Susan McKevitt lives in Bradford. On April 11, the New York Times ran an article entitled: “It’s Time to End the Quiet Cruelty of Property Taxes.” Like many towns, Bradford recently had its town meeting, and we experienced this cruelty.Over 200...

Business

BUSINESS QUARTERLY: Grants allow towns to study housing

In 2022 the State of New Hampshire, in recognition of the housing shortage in the state, created a grant program to fund work in towns that wished to explore the housing situation in their town and consider ways to increase housing availability and...

BUSINESS QUARTERLY: Dan Petrone – A guide to the commission settlement

BUSINESS QUARTERLY: Dan Petrone – A guide to the commission settlement

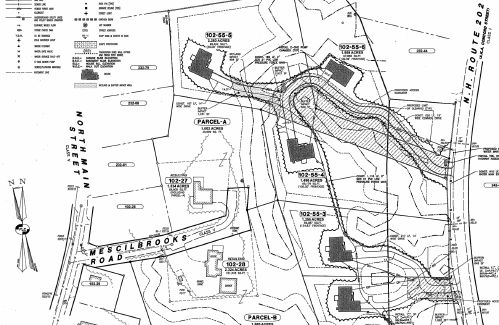

BUSINESS QUARTERLY – New housing projects could provide relief

BUSINESS QUARTERLY – New housing projects could provide relief

BUSINESS QUARTERLY – Antrim Planning Board approves Battaglia subdivision

BUSINESS QUARTERLY – Antrim Planning Board approves Battaglia subdivision

Arts & Life

Greenfield Roadside Roundup is April 27

The Greenfield Conservation Commission will hold its annual Roadside Roundup in honor of Earth Day Saturday, April 27, rain or shine.People can get their blue bags from the Recycling Center, Stephenson Memorial Library, Greenfield Post Office or...

Bernie Watson of Bernie & Louise dies at 80

Bernie Watson of Bernie & Louise dies at 80

Cosy Sheridan speaks and performs for Monadnock Writers’ Group

Cosy Sheridan speaks and performs for Monadnock Writers’ Group

‘The Last Laugh’ coming to Town Hall Theatre in Wilton

‘The Last Laugh’ coming to Town Hall Theatre in Wilton

Echoes of Floyd performs Saturday at Peterborough Town House

Echoes of Floyd performs Saturday at Peterborough Town House

Obituaries

Elizabeth "Betty" G. Mahon

Elizabeth "Betty" G. Mahon

Boscawen, NH - Elizabeth "Betty" G. Mahon, age 93, passed away peacefully on Saturday, April 13, 2024 with family by her side. She was born in Salem, MA daughter of the late John and Elizabeth (Tansey) Gannon. She was predeceased by he... remainder of obit for Elizabeth "Betty" G. Mahon

Phillip A. Avery

Phillip A. Avery

Bennington NH - Phillip A Avery, 81, of Bennington, peacefully passed away on April 4,2024 after a long and hard-fought battle with cancer, while under hospice care at Monadnock Community Hospital with his wife Ann and the love of his f... remainder of obit for Phillip A. Avery

Kevvin W. Sawtelle 31

Kevvin W. Sawtelle 31

Kevvin W. Sawtelle, 31 Jaffrey, NH - Kevvin W. Sawtelle, 31, of Rindge, died peacefully on April 5, 2024, in the arms of his family at the Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center in Lebanon, NH after a long battle with brain cancer. Kevvin w... remainder of obit for Kevvin W. Sawtelle 31

Constance Boldini

Constance Boldini

Westmoreland, NH - Constance Marie (Wilson) Boldini, died April 16, 2024. She is predeceased by her husband Guido Boldini and her son Peter Vaillancourt. She is survived by two daughters, Anne Young of Tennessee, Brenda Bryer of Stoddar... remainder of obit for Constance Boldini

T & W Handyman Services in Jaffrey celebrates new location

T & W Handyman Services in Jaffrey celebrates new location

BACKYARD NATURALIST: Phil Brown – Kestrel conservation expands in the Contoocook Valley

BACKYARD NATURALIST: Phil Brown – Kestrel conservation expands in the Contoocook Valley

Greenfield Community Power Committee approves identifying possible suppliers

Greenfield Community Power Committee approves identifying possible suppliers

Wilton Select Board discusses options for ARPA funds

Wilton Select Board discusses options for ARPA funds

The Rev. Barbara Thorngren of Temple works to build connections

The Rev. Barbara Thorngren of Temple works to build connections

HIGH SCHOOL SPORTS ROUNDUP: Tasha MacNeil leads the way for ConVal at Pelham Invita

HIGH SCHOOL SPORTS ROUNDUP: Tasha MacNeil leads the way for ConVal at Pelham Invita