Latest News

New photography studio opens on Jaffrey Main Street

New photography studio opens on Jaffrey Main Street

Jarvis Coffin: Off the Highway – Liver free or die

Jarvis Coffin: Off the Highway – Liver free or die

State of the Schools – Budget challenges, but lots to celebrate at Mascenic

I’m honored to have been asked to write a column highlighting the outstanding work of students and staff in the Mascenic Regional School District.This is my fifth year serving the communities of Greenville and New Ipswich. Despite the challenges of...

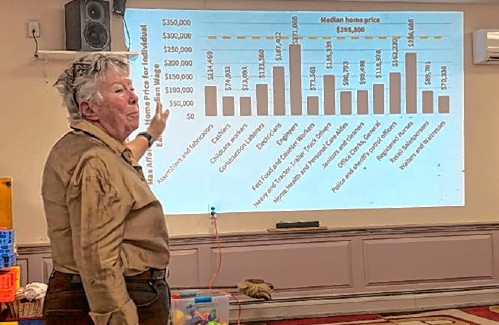

Frank Edelblut speaks at Dublin Education Advisory Committee forum

Speaking at a forum held by the Dublin Education Advisory Committee (DEAC) Tuesday night, New Hampshire Education Commissioner Frank Edelblut said it’s becoming increasingly common for towns to withdraw from their cooperative school districts.Edelblut...

Most Read

Petitioners seek special Town Meeting regarding tax lien on Antrim Church of Christ

Petitioners seek special Town Meeting regarding tax lien on Antrim Church of Christ

New photography studio opens on Jaffrey Main Street

New photography studio opens on Jaffrey Main Street

State of the Schools – Budget challenges, but lots to celebrate at Mascenic

State of the Schools – Budget challenges, but lots to celebrate at Mascenic

UPDATE: Drivers identified in Jaffrey dump truck crash

UPDATE: Drivers identified in Jaffrey dump truck crash

Frank Edelblut speaks at Dublin Education Advisory Committee forum

Frank Edelblut speaks at Dublin Education Advisory Committee forum

Editors Picks

ConVal committee begins to study withdrawal process

ConVal committee begins to study withdrawal process

HOMETOWN HEROES – Rose Novotny is motivated by community

HOMETOWN HEROES – Rose Novotny is motivated by community

New Ipswich firefighters called on to rescue horse

New Ipswich firefighters called on to rescue horse

Temple unlikely to hold special Town Meeting on ConVal withdrawal

Temple unlikely to hold special Town Meeting on ConVal withdrawal

Sports

After losing Borges, ConVal softball falls to H-B

Throw the final score out the window – ConVal’s 8-1 loss to visiting Hollis-Brookline Monday featured 7½ innings of playoff-caliber softball before being derailed by a shocking injury.“The bad part is nobody will know how great that game was if they...

Big first inning carries Wilton-Lyndeborough softball to win over Sunapee

Big first inning carries Wilton-Lyndeborough softball to win over Sunapee

Conant baseball shows its strength in win over Mascenic

Conant baseball shows its strength in win over Mascenic

Katalina Davis dazzles in Mascenic shutout win

Katalina Davis dazzles in Mascenic shutout win

Opinion

Viewpoint – Bridging the chasm of political polarization

Our founding document, the Declaration of Independence, opens with a national commitment to individual equality and rights, implicitly recognizing and protecting the diversity of America. Enabled by the declaration, we bring to our communities, our...

Letter: River Center thanks volunteers

Letter: River Center thanks volunteers

Business

T & W Handyman Services in Jaffrey celebrates new location

Downtown Jaffrey welcomed a new business last week, as T&W Handyman Services moved into a new location at 10 Stratton Road.Owners Tina and Wayne St. Laurent were joined by friends, family and Team Jaffrey members to celebrate the move from their...

BUSINESS QUARTERLY: Grants allow towns to study housing

BUSINESS QUARTERLY: Grants allow towns to study housing

BUSINESS QUARTERLY: Dan Petrone – A guide to the commission settlement

BUSINESS QUARTERLY: Dan Petrone – A guide to the commission settlement

BUSINESS QUARTERLY – New housing projects could provide relief

BUSINESS QUARTERLY – New housing projects could provide relief

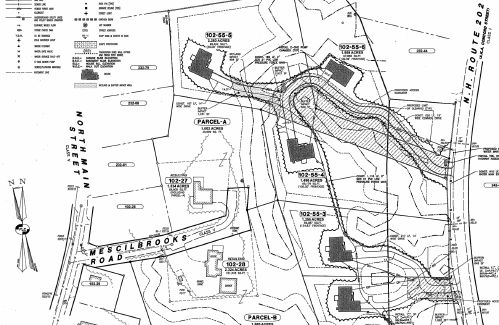

BUSINESS QUARTERLY – Antrim Planning Board approves Battaglia subdivision

BUSINESS QUARTERLY – Antrim Planning Board approves Battaglia subdivision

Arts & Life

Firelight Theatre co-founder Nora Fiffer takes ‘Another Happy Day’ to Beverly Hills Film Festival

One of Firelight Theatre’s founders, Nora Fiffer, will be discussing her drama "Another Happy Day" after it screens at the Beverly Hills Film Festival May 3.Fiffer began writing the screenplay for “Another Happy Day” when she moved to Peterborough in...

Francestown Academy Coffeehouse is in its second year

Francestown Academy Coffeehouse is in its second year

Jaffrey Civic Center hosting ‘Two Tours’ exhibit

Jaffrey Civic Center hosting ‘Two Tours’ exhibit

Ana Armengod showing experimental films for MacDowell Downtown

Ana Armengod showing experimental films for MacDowell Downtown

Monadnock Comic Con is May 3 and 4 in Jaffrey

Monadnock Comic Con is May 3 and 4 in Jaffrey

Obituaries

Betty S. S. Stoughton

Betty S. S. Stoughton

Jaffrey NH - Betty S. S. Stoughton died suddenly on April 13, 2024, a surprise to all who believed she'd live forever or at least until they were ready to say goodbye. She was born on October 16, 1927, fifth of six children born to ... remainder of obit for Betty S. S. Stoughton

Cynthia E. Hamilton

Cynthia E. Hamilton

Jaffrey, NH - Cynthia E. Hamilton, 92, a lifelong resident of Jaffrey, NH, passed away at Portsmouth Regional Hospital on Tuesday, April 23, 2024. Cynthia was born in Peterborough, NH, on May 4, 1931, daughter of the late Don A. and... remainder of obit for Cynthia E. Hamilton

Dorothy Record

Dorothy Record

Dorothy 'Pearl' Record Jaffrey NH - With her family by her side, Dorothy "Pearl" Record, 84, passed away peacefully on Saturday, April 27, 2024, at the Jaffrey Rehabilitation & Nursing Center in Jaffrey, NH, after a lengthy battle with A... remainder of obit for Dorothy Record

Maxine Teates

Maxine Teates

Maxine "Wickie" Teates Greenfield NH - Maxine L. "Wickie" Teates passed away peacefully, and surrounded by the love of her family, on April 27, 2024, at Spring Village at Summerhill in Peterborough. Wickie was born in Peterborough on Ap... remainder of obit for Maxine Teates

Gail Hoar: Words About Wilton – Lessons while walking

Gail Hoar: Words About Wilton – Lessons while walking

Restorative justice author Leaf Seligman to speak at the Mariposa Museum

Restorative justice author Leaf Seligman to speak at the Mariposa Museum